Rain hammered against the courthouse windows like impatient fists.

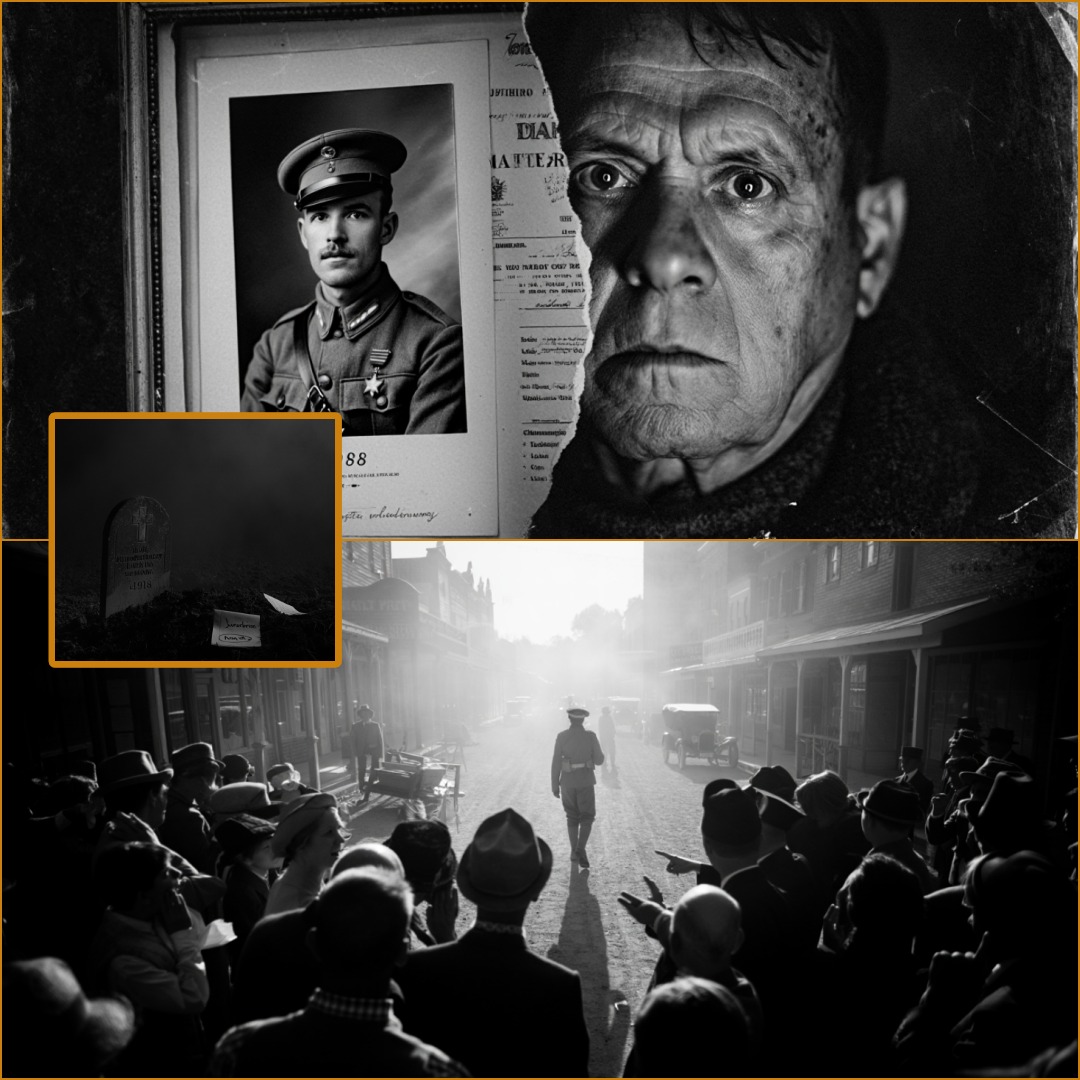

Inside the records room, the air was thick with dust and disbelief. Papers trembled atop the long oak table as an archive box—its cardboard softened by a century of neglect—was pried open. The metal hinges screamed, a sound so sharp it cut through the murmurs of the assembled officials.

Stamped across the folders inside, in ink faded to the colour of dried blood, were the words:

KIA – 1918.

Every breath in the room caught at once.

Mayor Harold Aldrich leaned forward, his glasses sliding down the bridge of his nose. He hadn’t meant to stay long. The box was supposed to contain nothing more than duplicated wartime casualty reports—documents to be digitised and forgotten. But something about the weight of the silence had pulled him closer.

His fingers brushed brittle paper, careful, almost reverent.

Then they stopped.

A name stared back at him.

Mercer, Elias.

The room erupted.

“That’s not possible,” someone whispered.

Another voice, louder, cracked. “We buried him.”

They had. The entire town had.

Elias Mercer had been laid to rest forty years earlier, beneath a gray stone on the northern hill. His parents had chosen the spot themselves, overlooking the river where he’d fished as a boy. The church bell had tolled. Candlelight vigils had burned through three nights of summer rain. Children had grown up hearing the story of the brave young man lost in the final months of the Great War.

Elias Mercer, killed in France, 1918.

Except the ledger didn’t list him among the dead.

It listed him as reassigned.

A Death Everyone Remembered

Elias had been nineteen when he left town.

Tall, soft-spoken, with a habit of tipping his hat to everyone he passed, he boarded the train in April 1918 with a knapsack his mother had stitched herself. He promised he’d be back by harvest. He promised he’d write every week.

The letters stopped in October.

Two weeks later, the telegram arrived.

We regret to inform you…

His mother collapsed before she reached the final line. His father stood frozen, holding the paper like it might burst into flames.

The town grieved collectively. Elias had been one of theirs—the boy who fixed fences for widows, the young man who stayed late after church to stack chairs. When the war ended weeks later, his death became part of the town’s sorrowful pride. They told themselves he’d helped end it.

No body ever came home. The war had taken too many. The grave marker stood in for absence.

And that was how history settled.

Until the box was opened.

The Record That Shouldn’t Exist

The clerk who found the ledger, a woman named June Holloway, would later say she almost closed the box again. Something in her gut told her it wasn’t meant to be seen.

But procedure won.

The entry was clear.

Mercer, Elias — reassigned November 3, 1918. Status: Classified.

There was a second page.

A fingerprint smudged the margin, as though someone had hesitated while writing it.

Declared deceased for operational purposes.

The phrase rippled through the room like a curse.

Declared.

Not killed.

Mayor Aldrich ordered the room cleared. By sundown, only three people remained: the mayor, June Holloway, and Professor Thomas Keene, the town’s unofficial historian.

Keene was pale, his hands shaking.

“There were rumours,” he said quietly. “After the war. Men who never came home but weren’t on any battlefield rolls. People said they were nonsense. Ghost stories.”

“What kind of men?” Aldrich asked.

Keene swallowed. “The ones who knew too much.”

A Second Life in the Shadows

The deeper they searched, the stranger it became.

Military correspondence referenced Elias only by initials after November 1918. Locations were redacted. Units unnamed. One memo described him as “compliant but resistant to reintegration.”

Another stated flatly: Subject may not be released. Civilian life no longer viable.

There was no record of discharge.

No death certificate.

Just silence.

Until 1937.

A hospital intake log from three states away listed an unnamed man with shrapnel scars, a damaged lung, and hands that shook uncontrollably. Under “Next of Kin,” a single word was written:

None.

The attending nurse had scribbled a note in the margin:

Patient insists he already died once.

The Grave on the Hill

Word spread by morning.

People gathered at the cemetery before the mayor could stop them. Rain soaked coats. Mud clung to shoes. Someone placed fresh flowers on Elias’s stone, though no one knew why.

The question hung in the air:

If he didn’t die in 1918… who was buried here?

Permission was granted by noon.

The dig was shallow. The casket was old, the wood warped. When it was opened, the crowd recoiled.

Inside lay bones—but not Elias’s.

Dental records confirmed it later. The remains belonged to a man nearly ten years older, with injuries inconsistent with combat. No one recognised the name found on a fragment of cloth tucked inside the jacket.

Someone had been given Elias’s death.

And Elias had been given something else.

The Letter That Changed Everything

It was June Holloway who found the letter.

Tucked inside a false bottom of the archive box, sealed in oilskin, was a single envelope. The handwriting was shaky but unmistakable.

To whoever still remembers me,

If you are reading this, then I have failed to stay erased.

I did not die in France. I was ordered not to live at home.

They told me it was temporary. That the truth would surface when the time was right. But time kept moving, and I stayed frozen.

I watched the world change from rooms with no windows. I signed papers with names that weren’t mine. I was alive only on borrowed breath.

Please tell my parents I thought of them every day.

The letter ended without a signature.

But the fingerprint on the wax matched the one in the ledger.

The Man Who Lived Too Long

Records eventually revealed Elias had been used as part of a post-war intelligence operation—one that collapsed under its own secrecy. The men involved were deemed expendable not because they failed, but because they knew the truth of what had happened after the armistice.

They were easier to bury than explain.

Elias survived into old age, drifting between hospitals, government facilities, and anonymity. His death—his second one—came quietly in 1962 under a name no one recognised.

No stone marked it.

What the Town Learned Too Late

On the anniversary of his supposed death, the town gathered again on the northern hill.

They added a second plaque beneath the original stone.

Elias Mercer

1899–1962

Soldier. Son. Survivor.

Children listened as elders told the story differently now. Not of a boy who died young, but of a man who lived with a truth too heavy to carry home.

Some said the town had failed him.

Others said the world had.

As dusk fell, the church bell rang once.

Not for a death.

But for a life finally acknowledged.

And in the quiet that followed, many swore they felt it—the strange relief of a soldier who, after dying twice, was at last allowed to rest.