The tragic death of Piper James on K’gari (formerly Fraser Island) has highlighted not only the risks of human-wildlife interactions but also the unusual group dynamics sometimes displayed by the island’s dingoes. Officials have confirmed that between eight and ten wild dingoes were present in the area that fateful morning, yet rangers noted something striking: it was unusual for them to be huddled so closely together when her body was discovered on the sand.

The Scene: A Pack in Uncharacteristic Proximity

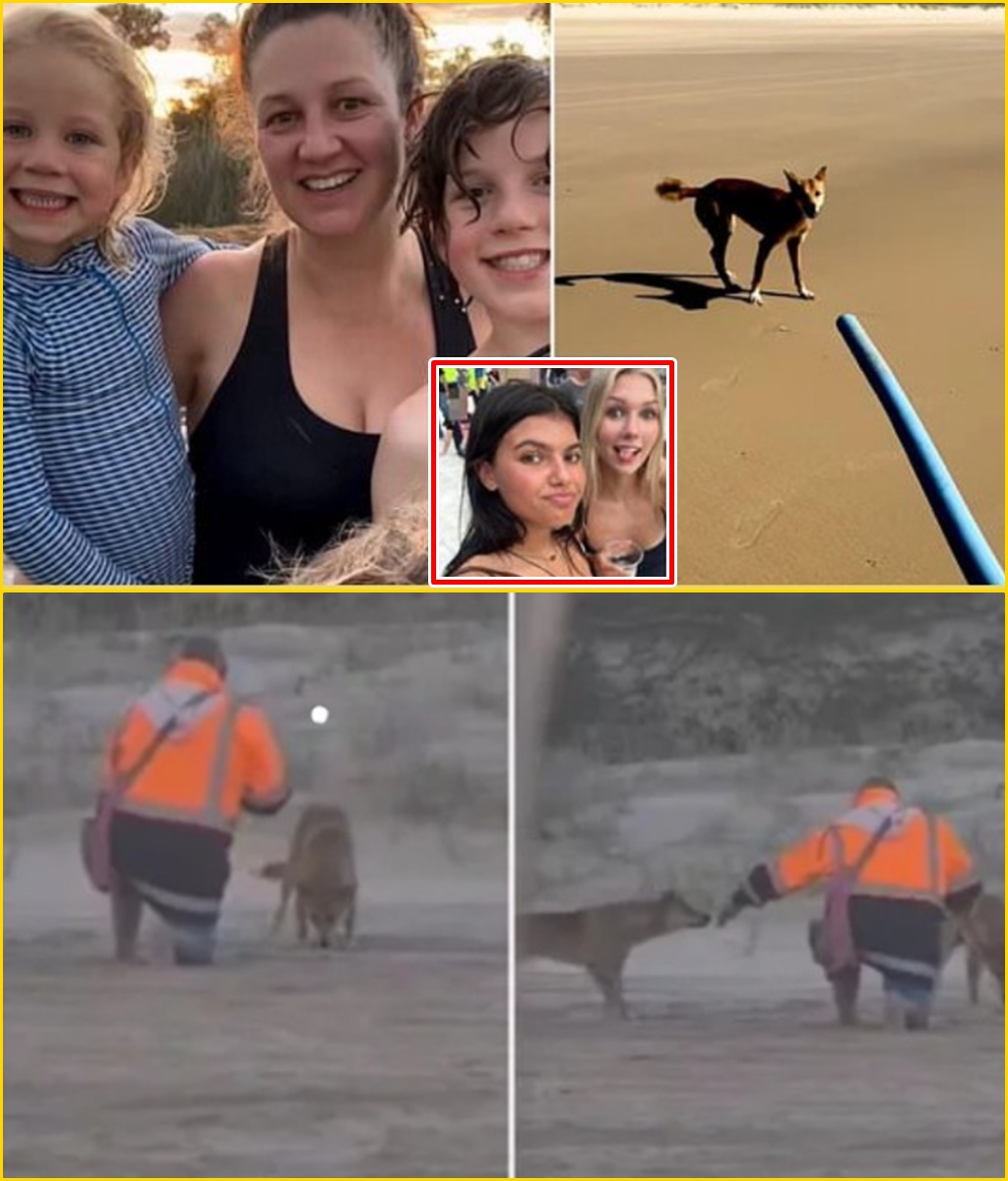

When two men driving along the eastern beach spotted the group shortly after 6:30 a.m. on January 19, 2026, they initially saw about 10 dingoes clustered tightly around an object. As the vehicle approached, the animals dispersed, revealing the body of the 19-year-old Canadian backpacker. This tight huddle — rather than the more typical dispersed foraging or patrolling behavior — stood out to experienced rangers and locals familiar with K’gari’s wongari (the Butchulla name for dingoes).

Dingoes on the island usually operate in smaller family units or alone, especially during daylight hours. Large packs forming and maintaining close proximity, particularly around a single point for an extended period, is not routine. Rangers monitoring the animals in the days following the incident described the pack’s behavior as aggressive in subsequent encounters, including one observed toward a camper. This led authorities to classify the group as posing an unacceptable public safety risk, prompting the decision to euthanize them — with six already culled by late January 2026, and more planned.

The close grouping raised questions about what drew and held the dingoes together. Preliminary autopsy findings from the Queensland Coroners Court pointed to drowning as the most likely primary cause of death, with pre-mortem injuries consistent with dingo bites (occurring while she was alive) but deemed unlikely to have caused immediate fatality. Extensive post-mortem bite marks suggested the animals interacted with her remains after death. This has fueled speculation that the dingoes may have been drawn to her while she was in distress in the water or on the shore, then remained clustered as they fed or investigated.

Why the Huddle Was Unusual — and What It Might Mean

Experts on dingo behavior note that while packs can form for hunting or defense, sustained close huddling around a stationary human is rare and often linked to habituation — dingoes losing natural fear of people due to feeding, close approaches for photos, or other tourist interactions. On K’gari, home to one of Australia’s purest dingo populations (estimated at 100–200 individuals), such boldness has increased amid rising visitor numbers and overtourism concerns.

Previous incidents on the island have involved packs chasing or corralling people toward the water — a tactic seen in a 2023 case where a jogger was forced into the surf by dingoes. In Piper’s case, her father, Todd James, suggested the animals may have viewed her as vulnerable prey — alone, splashing in the shallows at dawn — prompting them to approach and potentially push her farther out, leading to drowning. The tight grouping when discovered could indicate lingering interest in what they perceived as a food source or an opportunistic gathering around an immobile figure.

Rangers and wildlife officials emphasized that the pack’s behavior post-incident — including continued aggression — justified removal, though critics, including dingo geneticists and Butchulla traditional owners, argue culling an entire family group risks destabilizing the population’s already low genetic diversity and could create an “extinction vortex” without addressing root causes like tourism management.

Broader Implications for K’gari’s Dingoes and Visitors

K’gari’s dingoes are culturally sacred to the Butchulla people and protected under its World Heritage status. Yet fatal or near-fatal interactions remain exceptionally rare — the last confirmed dingo-related human death on the island was in 2001. The increase in aggressive encounters is widely attributed to habituated animals rather than inherent aggression.

The Piper James case has intensified calls for better education, stricter rules against feeding or approaching dingoes, and possibly capping visitor numbers during peak seasons. Her family, while devastated, has expressed that Piper — an animal lover who worked with wildfires and adored the outdoors — would not have wanted the dingoes harmed because of what they see as her own misjudgment in venturing out alone without precautions like carrying a stick for deterrence.

As the coronial inquest continues and final pathology results are awaited, the image of eight to ten dingoes huddled unusually close remains a poignant and unsettling detail — a reminder of how quickly a peaceful sunrise swim can turn tragic when wild instincts meet human vulnerability on one of Australia’s most pristine yet perilous landscapes.

The grief for Piper endures, as does the urgent debate: how to keep both people and dingoes safe in a shared space where neither should ever feel entirely at ease.