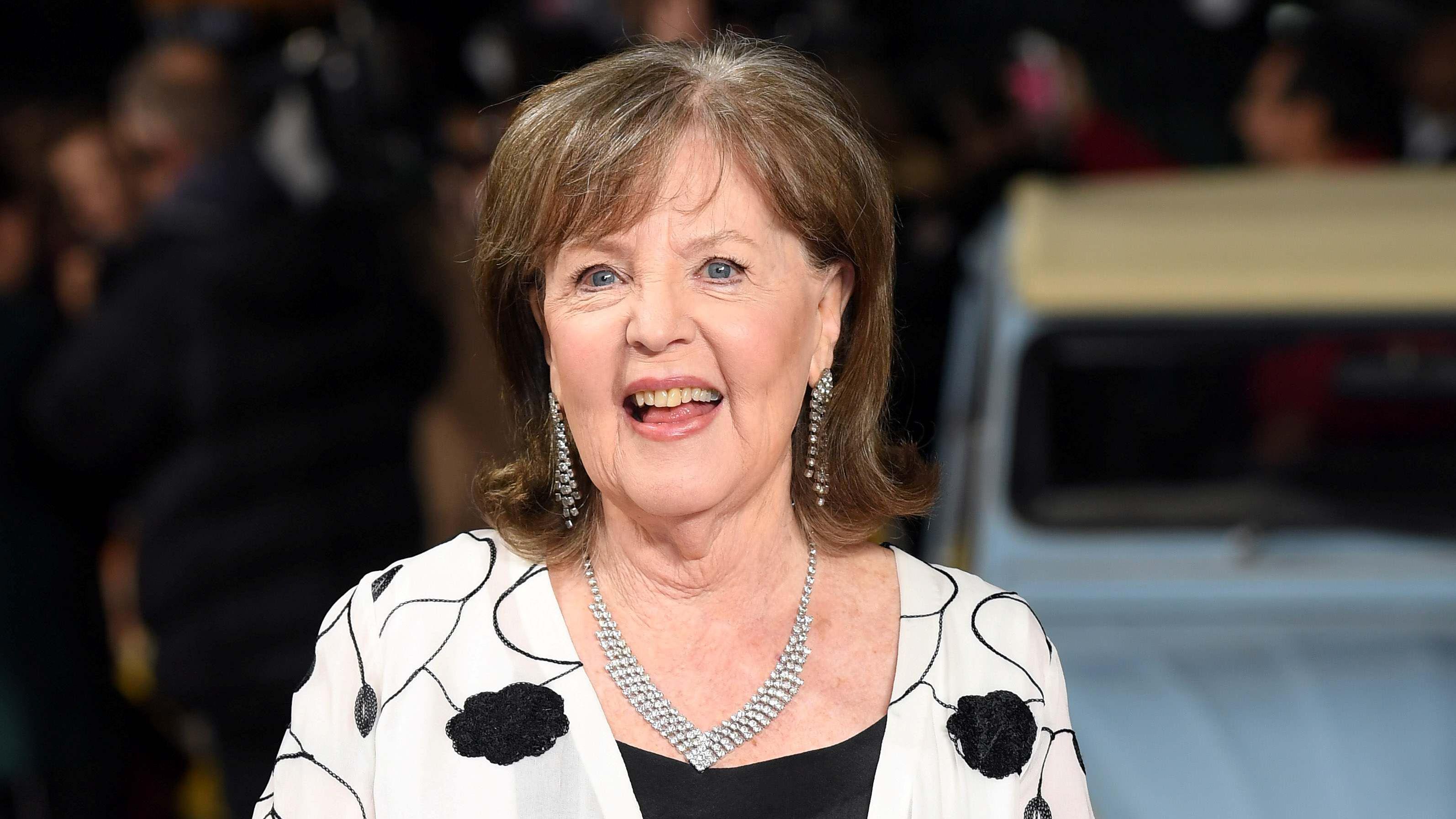

Tributes Pour In as Shirley Valentine Star Pauline Collins Passes Away at 85

LONDON – The British theatre and film world is in mourning following the death of Pauline Collins, the effervescent actress whose portrayal of the indomitable housewife Shirley Valentine captivated audiences on stage and screen, earning her an Oscar nomination and a lasting place in the nation’s heart. Collins, who had been living with Parkinson’s disease for several years, died peacefully on November 5, 2025, at her care home in Highgate, north London, aged 85. Surrounded by her loving family, she slipped away with the same quiet dignity that defined her remarkable life.

In a poignant statement released to the press, Collins’s family expressed their profound grief while celebrating her indomitable spirit. “We are heartbroken to announce that Pauline Collins died peacefully at her care home in Highgate this week, having endured Parkinson’s for several years,” they said. “She was a bright, sparky, witty presence on stage and screen, and she will always be remembered as the iconic, strong-willed, vivacious, and wise Shirley Valentine.” The words echoed the warmth and resilience that made Collins a beloved figure, not just as an performer, but as a wife, mother, and storyteller of the human condition.

Born Pauline Angela Collins on September 3, 1940, in the seaside town of Exmouth, Devon, she was the daughter of William Henry Collins, a school headmaster and wartime tank instructor, and Mary Honora Callanan, a dedicated schoolteacher. Her early years were marked by the upheavals of World War II. Raised initially in Wallasey, across the Mersey from Liverpool, the family home was destroyed in a bombing raid, prompting a return to the south-west. Post-war life saw them shuttling between Wallasey and Battersea, where her father took up his headmaster role and her mother taught at a Catholic school. Educated at the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Hammersmith, Collins initially pursued a career in education, training at the Central School of Speech and Drama and working briefly as a supply drama teacher. But the pull of the footlights proved irresistible; by her early twenties, she had abandoned the classroom for the capricious world of acting.

Collins’s breakthrough came in the early 1970s with her role as Sarah Moffat, the cheeky and ambitious parlourmaid in the groundbreaking ITV series Upstairs, Downstairs. Airing from 1971 to 1975, the show offered a sharp, satirical lens on Edwardian class divides, and Collins’s Sarah – a woman navigating the treacherous waters of servitude while harbouring dreams of social ascent – became an instant icon. Her character’s ill-fated affair with the aristocratic James Bellamy (Simon Williams) culminated in a heartbreaking storyline: the stillbirth of her son. Yet, it was in the spin-off series Thomas & Sarah (1979), where she reunited on screen with her real-life husband John Alderton as the chauffeur Thomas Watkins, that their chemistry truly sparkled. The couple’s easy rapport, forged in both art and life, endeared them to viewers, blending domestic farce with poignant social commentary.

Marriage to Alderton, whom she wed in 1969 after meeting on the set of Upstairs, Downstairs, was the anchor of Collins’s personal world. The pair settled in the leafy enclave of Hampstead, London, raising three children: Nicholas, Kate, and Richard. Their family life, often described as blissfully ordinary amid the glamour of showbusiness, was a testament to Collins’s grounded nature. “Pauline was the heart of our home,” Alderton said in a tribute shared via the family statement. “A remarkable star on stage, but an even more devoted wife and mother off it. Her laughter filled our house, and her wisdom guided us all.” Yet, Collins’s family story carried layers of complexity and courage. Before her marriage, in 1964, she had given birth to a daughter, Louise, with actor Tony Rohr during a fleeting relationship. Facing societal pressures and the demands of a nascent career, Collins made the agonising decision to place Louise for adoption. The reunion, when Louise turned 21, was a cathartic turning point, immortalised in Collins’s candid 1992 autobiography, Letter to Louise. The book, blending memoir and epistolary reflection, explored themes of regret, redemption, and maternal love with unflinching honesty. “It was the hardest letter I ever wrote,” Collins once reflected in an interview, “but it healed wounds I didn’t know were still bleeding.”

Professionally, the 1970s cemented Collins’s status as a versatile force. She brought her trademark wit to the scatty, lovable Clara Danby in the BBC sitcom No – Honestly (1974-1975), opposite Alderton again, whose scatterbrained antics masked a deeper warmth that won her legions of fans. A foray into music even ensued: Collins recorded the novelty single “What Are We Going to Do with Uncle Arthur?” – a ditty performed by her Upstairs, Downstairs character – which charted modestly but captured her playful side.

The role that would define her legacy arrived in 1988 with Willy Russell’s one-woman play Shirley Valentine. Premiering at London’s Vaudeville Theatre, it was a tour de force: a two-hour monologue delivered by a fortysomething Liverpool housewife, chafing against the drudgery of married life in a terraced house, dreaming of escape to sun-drenched Greece. Collins infused Shirley with raw authenticity – the stretch marks, the self-deprecating Scouse humour, the quiet rage against unfulfilled potential. Critics raved; The Guardian’s reviewer hailed her final act as evoking “a real woman, all stretch-mark and lobster-pink tan, acknowledging she is full of unused life.” The production ran for a sold-out year in the West End, earning Collins the Olivier Award for Best Actress. She then triumphed on Broadway at the Booth Theatre in 1989, securing a Tony Award and running for 10 months to ecstatic houses.

Hollywood beckoned with the 1989 film adaptation, directed by Lewis Gilbert and scripted by Russell. Starring alongside Tom Conti as Shirley’s Greek paramour Costas and Bernard Hill as her hapless husband Joe, Collins reprised the role with electric vitality. Paramount Pictures initially pushed for a bigger American name, but Russell held firm: “It’s Pauline or no one.” Her performance – a masterclass in comic timing and emotional depth – garnered an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress, as well as a Golden Globe nod. At the Oscars, she lost to Jessica Tandy’s Driving Miss Daisy, but the recognition affirmed her as a global talent. “Shirley wasn’t just a role,” Collins said in a 1990 interview. “She was every woman who’d ever felt invisible. Playing her was like holding up a mirror to my own life – the joys, the frustrations, the sheer bloody cheek of it all.”

Collins’s career never rested on laurels. The 1990s and beyond saw her embrace diverse challenges. In City of Joy (1992), she supported Patrick Swayze in Roland Joffé’s tale of resilience amid Calcutta’s slums. My Mother’s Courage (1995) drew on Holocaust survivor stories, showcasing her dramatic range. Perhaps most poignant was Paradise Road (1997), Bruce Beresford’s harrowing depiction of women in a Japanese POW camp during WWII. As Mrs. Roberts, Collins helped form a vocal orchestra to defy their captors, her performance earning acclaim for its quiet defiance – a role that resonated with her own wartime childhood scars.

Television remained a touchstone. She starred as the formidable Harriet Smith in the BBC’s The Ambassador (1998-1999), navigating diplomatic intrigue with acerbic flair. Later, she guested in The Royle Family and The Last Detective, her cameos infused with that signature sparkle. Films like Mrs Caldicot’s Cabbage War (2002) reunited her with Alderton in a tale of elderly rebellion, while Albert Nobbs (2011) and Quartet (2012) – Dustin Hoffman’s directorial debut – highlighted her enduring elegance. Her final screen role came in 2017’s The Time of Their Lives, a road-trip comedy opposite Dame Joan Collins, playing a retired actress scattering ashes in France. “Age is just a number,” she quipped at the premiere. “It’s the fire inside that counts.”

Honours followed her trailblazing path. In 2001, she was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for services to drama, a nod to her boundary-pushing portrayals of working-class women. Yet, Collins shunned the spotlight’s glare, preferring the intimacy of family and script-reading marathons with Alderton. Parkinson’s diagnosis in her later years slowed her, but never dimmed her zest. She continued sporadic appearances, advocating quietly for the condition’s research.

Tributes have flooded in from across the arts. Dame Joanna Lumley, who co-starred with her in Shirley Valentine, called Collins “a luminous force, all wit and wonder. She taught us how to laugh at life’s absurdities while embracing its depths.” Director Lewis Gilbert’s estate remembered her as “the soul of the film – irreplaceable.” Willy Russell, Shirley’s creator, posted on social media: “Pauline didn’t just play her; she became her. A national treasure, gone too soon.”

Collins’s death comes at a time when British theatre grapples with funding cuts and post-pandemic recovery, but her legacy endures as a beacon of unapologetic femininity and northern grit. As her family noted, she was “so many things to so many people.” Survived by Alderton, their three children, Louise, and grandchildren, Pauline Collins leaves a world richer for her having danced through it – lobster-pink tan and all.