A Childhood Behind Barbed Wire: Joyce Nakamura Okazaki Recalls Life Inside Manzanar and Being Photographed by Ansel Adams

When Joyce Nakamura Okazaki was just 7 years old, she was taken with her family to a place she had never heard of—an isolated desert compound ringed with barbed wire, watched over by armed guards, and governed by rules she didn’t understand. She remembers being told not to approach the perimeter fence because soldiers had orders to shoot anyone who came too close.

She had committed no crime. Nor had her parents, nor her older sister. The Nakamura family, all of them American citizens, were among the more than 120,000 Japanese Americans who were forcibly removed from their homes during World War II and incarcerated in government-run camps. For two years, the desert outpost called the Manzanar War Relocation Center became their involuntary home.

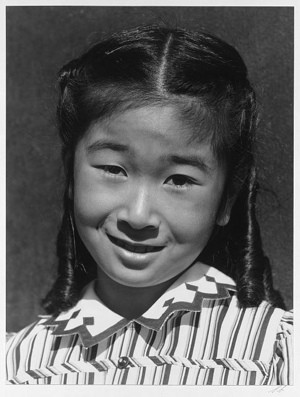

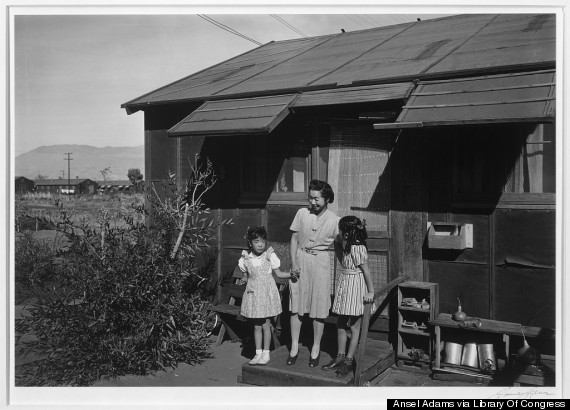

Those years would stay with Okazaki for the rest of her life, even if she didn’t yet fully understand their meaning. In 1943, a year after she arrived, the celebrated photographer Ansel Adams visited Manzanar to document camp life. Among the many scenes he captured was a photograph of Okazaki, her sister Louise, and their mother—a family caught in a moment of quiet resilience amid harsh surroundings.

Decades later, when Adams’ book Born Free and Equal was republished in 2001, one of those images—featuring Joyce herself—was selected for the cover. That decision would reshape the trajectory of Okazaki’s life, compelling her to speak publicly about an experience many survivors once felt pressured to bury.

“It made me feel like I should do something,” she said. “If my face is there, I need to make sure people know what happened at Manzanar.”

Today, Okazaki serves as the treasurer of the Manzanar Committee, the nonprofit responsible for educating the public about Japanese American incarceration and preserving Manzanar as a site of memory and reflection.

In a recent conversation with HuffPost, Okazaki revisited her earliest memories of displacement—memories that remain vivid despite the passage of nearly eight decades.

“I had no idea. I just went with my mother.”

Okazaki says she was given no explanation when her family was forced to leave their home in Los Angeles’ Boyle Heights neighborhood. She was too young to understand the politics of war, prejudice, or executive orders. What she remembers is simply being taken.

“I had no idea,” she said. “I don’t think they told us because we were so young.”

What she does recall is waiting by the railroad tracks near Union Station in Los Angeles, surrounded by other families and watched closely by soldiers carrying rifles.

“I asked my mother why we had to stand there,” she said. “She never replied.”

The family eventually boarded a train with the shades pulled down—a common practice intended to hide the forced relocation from public view. The journey was long, disorienting, and silent. When they finally arrived, they were packed into Army trucks and driven through the darkness to a place Joyce had never seen.

“There were ditches all over,” she recalled. “They were putting in sewer lines and water lines. I didn’t know where we were. I was probably a little scared because everything was unfamiliar.”

Only later, long after she had begun living behind barbed wire, did she learn the name of the place: Manzanar.

Life Behind Barbed Wire

For Okazaki, childhood became something very different from what she had known. The desert was harsh, the dust storms constant, the barracks cramped and poorly insulated. Privacy was nonexistent, and the presence of guards—and the threat implied by their guns—was a daily reminder that she was being held against her will.

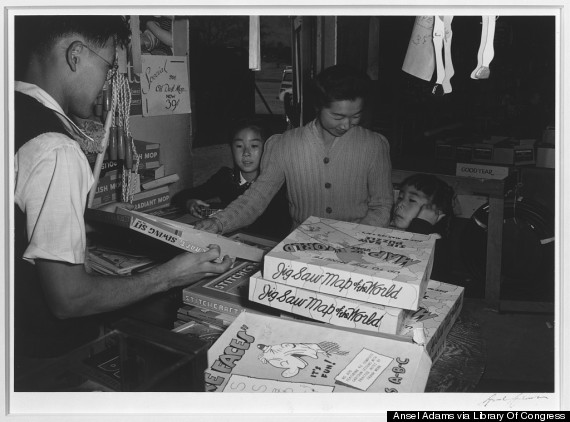

Yet like many children in the camps, she also adapted. She attended school, played with other children, and learned to navigate the routines of a place designed to confine.

“I didn’t understand why we were there,” she later said. “But I knew not to go near the fence.”

A Photographer’s Visit

When Ansel Adams arrived at Manzanar in 1943, he sought to capture not the bleakness of incarceration, but the humanity of the people enduring it. His portraits—simple, striking, dignified—became some of the most important visual records of the camp.

For Okazaki, being photographed was not particularly memorable at the time. But decades later, seeing her childhood self on the cover of Adams’ republished book stirred something deep.

“It felt like a responsibility,” she said. “If I’m on that cover, I need to speak. I need to help make sure this history isn’t forgotten.”

A Legacy of Memory

Today, as a leader in the Manzanar Committee, Okazaki helps organize educational programs, pilgrimages, and preservation efforts. She speaks to students, historians, and the public about her experience—not for herself, she says, but for the generations who must understand the fragility of civil liberties.

Her message is consistent and clear:

What happened at Manzanar was a failure of justice, and remembering it is essential to preventing it from happening again.

“I was 7 years old,” she said. “We were American citizens. And we were put behind barbed wire.”