November 1943. The war in the Pacific had become a butcher’s ledger. Every island taken meant thousands of names scratched off the rolls. Tarawa, just weeks earlier, had cost the United States Marine Corps 1,009 dead and 2,101 wounded for a coral speck the size of Central Park. The Japanese lost 4,690 out of 4,690. They died where they stood, in bunkers, in spider holes, in the surf, believing their sacrifice would force America to the negotiating table.

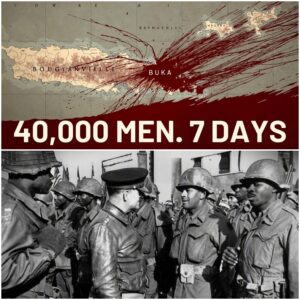

Now the map showed the next target: Bougainville.

Bougainville was not a speck. It was the largest island in the Solomon chain – 6,000 square miles of volcanic mountains, impenetrable jungle, mangrove swamps, and malaria-ridden rivers. The Japanese had turned it into the crown jewel of their outer defense line. Forty thousand troops – the cream of the Imperial Navy’s Special Naval Landing Forces and the Army’s 6th Division – waited behind concrete casemates, coastal guns, minefields, and four major airfields. Supply dumps brimmed with rice, ammunition, and medicine. General Hyakutake Haruyoshi, the defender of Guadalcanal, commanded them personally. His orders from Tokyo were simple: hold Bougainville at all costs. Make the Americans pay in blood until they lost the will to fight.

Imperial Headquarters called it the Z Plan: a ring of “unsinkable aircraft carriers” from which the Combined Fleet would sail out for the final, decisive battle. Bougainville was the northern anchor of that ring. Tokyo calculated that the Americans, wedded to frontal assault and overwhelming force, would have no choice but to storm the island head-on. The projected cost: 10,000–15,000 American dead. Acceptable, if it broke the Allied advance.

But two men in Pearl Harbor looked at the same map and asked the question that would bury the Z Plan forever.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief Pacific Fleet, leaned over the chart table and tapped Bougainville with a pencil.

“Why do we have to take the whole damn island?”

Beside him, General Douglas MacArthur – technically Nimitz’s rival, but temporarily allied for this campaign – gave a wolfish grin.

“Because the Japanese think we’re stupid enough to try.”

They weren’t.

The plan they devised was radical, almost cruel in its simplicity. They would not invade Bougainville proper. They would seize only the narrow western beachhead at Empress Augusta Bay – just enough land to build an airfield. Then they would seal the island like a tomb. No supplies in. No troops out. The 40,000 Japanese would be left to starve, rot, and die in the jungle while the war moved on without them.

It was war by calorie restriction.

Phase One – The Landing 1 November 1943

At 0730 the 3rd Marine Division hit Cape Torokina under a hurricane of naval gunfire. The Japanese, expecting the main assault in the south near Buin, were caught flat-footed. By nightfall the Marines had a shallow perimeter 4,000 yards wide and 2,000 yards deep – a postage stamp on a continent-sized island.

The Japanese reacted with fury. Hyakutake hurled 15,000 men at the beachhead in suicidal night attacks. They came screaming “Banzai!” through the swamps, only to be cut down by machine guns and artillery firing point-blank. The Marines held. By November 8 the perimeter was secure.

Phase Two – The Air Hammer 11–18 November 1943

While the Marines dug in, the U.S. Fifth Air Force turned its attention 210 miles north to Rabaul – the great Japanese supply base on New Britain. Rabaul was the artery that fed Bougainville. Cut it, and the island dies.

For seven straight days, waves of B-24 Liberators, B-25 Mitchells, and P-38 Lightnings hammered the harbor. They came at dawn, at noon, at dusk. They sank twelve transports, eight destroyers, and 52,000 tons of merchant shipping. They cratered the airfields, destroyed 200 aircraft on the ground, and turned the docks into burning wreckage. Japanese Admiral Kusaka sent frantic pleas to Tokyo: “Rabaul is finished. No more supplies can reach Bougainville.”

Tokyo’s reply was silence.

Phase Three – The Tomb Closes December 1943 – August 1945

With Rabaul neutralized, Bougainville was marooned. No ships dared the 400-mile run from Truk through waters patrolled by American submarines and carrier aircraft. Submarines sank the few barges that tried. By January 1944 the garrison’s daily rice ration had fallen from 800 grams to 200. By March it was 100. By June it was zero.

The jungle, once an ally, became executioner.

Malaria, dengue, beriberi, and dysentery swept the ranks. Men’s legs swelled to twice their size from vitamin deficiency. Teeth fell out. Skin split open. Soldiers ate grass, roots, leather belts, even the bark of trees. Cannibalism began in isolated outposts. Diaries later recovered told of men drawing lots to see who would be eaten first.

General Hyakutake, once proud commander of the “invincible” 17th Army, wrote in his journal: “We have become ghosts haunting our own graves.”

The Americans never launched a major ground offensive. They simply waited. Patrols probed the perimeter, picking off foraging parties. Occasionally a Japanese battalion would attempt a breakout, only to be shredded by artillery pre-registered on every trail. The Marines called it “mowing the lawn.”

By the time Japan surrendered in August 1945, only 15,000 of the original 40,000 defenders remained alive – gaunt, ragged, many too weak to walk. They staggered out of the jungle carrying white flags made from rice sacks, eyes hollow, uniforms rotting off their bodies. The rest – 25,000 men – had been claimed not by bullets, but by the “war of calories.”

The Green Tomb had done its work.

Epilogue

When the first American occupation troops finally marched into the southern strongholds in September 1945, they found a landscape out of Dante. Bunkers full of skeletons still clutching rifles. Airfields overgrown with vines. A hospital cave containing 800 dead, laid out in neat rows as if waiting for a doctor who would never come.

In one command bunker they discovered General Hyakutake’s body. He had committed seppuku on August 18, 1945 – three days after the Emperor’s surrender broadcast – rather than face the shame of captivity.

His final diary entry, dated the day he died, read:

“We were ordered to die gloriously. Instead we died slowly, forgotten by our own nation, starved by an enemy who never even deigned to fight us. The Americans did not defeat us with courage. They defeated us with arithmetic.”

The arithmetic was merciless: 40,000 men removed from the war at the cost of 312 American dead in the Cape Torokina perimeter – most from the initial landing.

Bougainville became the template. Truk, Rabaul, Wewak, all the “invincible” fortresses were bypassed, isolated, and left to rot. Hundreds of thousands of Japanese soldiers were erased from the war map without the United States ever having to storm their beaches.

The Japanese called it “the victory disease” – the arrogance that made them believe the enemy would always play by their rules.

America’s answer was colder, cleaner, and utterly devastating:

We don’t have to play at all.

We just walk away… and let the jungle finish the job.