Netflix’s limited series Vladimir, which premiered on November 14, 2025, marks one of the most intelligent and unsettling political thrillers of the streaming era. Adapted from Julia May Jonas’s acclaimed 2022 novel and executive produced by Rachel Weisz herself, the six-episode drama stars Weisz in a career-defining performance as Professor Nina, a tenured literature professor at an elite East Coast university whose life unravels when her husband John — also a professor — is accused of sexual misconduct by multiple female students.

The story unfolds through Nina’s increasingly fractured perspective. At first, she is the supportive, liberal-minded wife who believes in due process and presumes innocence. But as the allegations mount, as colleagues distance themselves, as her own students begin to question her silence, Nina’s worldview begins to crack. What starts as private doubt grows into public complicity, then quiet rage, and finally a chilling moral reckoning. The series never lets Nina — or the viewer — off the hook. Every choice she makes is compromised; every justification she offers is hollow.

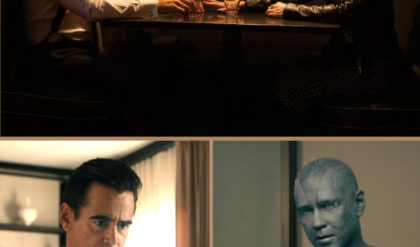

Weisz is extraordinary. She plays Nina with a stillness that borders on terrifying — a woman who has spent decades perfecting composure, now watching that composure become a cage. Her performance is built on micro-gestures: a too-long pause before answering a colleague’s question, a flicker of disgust when she hears her husband’s name, the way her hands tremble when she pours wine she no longer tastes. It is a masterclass in repression — the kind of acting that makes silence louder than shouting.

The supporting cast is equally strong. Jay Duplass plays John with unnerving plausibility — charming, wounded, never quite villainous enough to make moral judgment easy. The ensemble of students (led by a standout turn by Sophia Lillis as the most outspoken accuser) feels authentically generational: angry, articulate, and unwilling to accept half-measures. Toby Huss brings dry menace as the university’s dean, a man who cares more about optics than justice.

Visually, Vladimir is stark and deliberate. Director Sarah Adina Smith (who helmed all six episodes) uses cold, muted palettes — institutional grays, wintry whites, sterile lecture halls — to mirror Nina’s emotional frost. The camera lingers on empty corridors, half-read emails, and half-finished sentences, letting tension build through absence rather than action. The score, composed by Hildur Guðnadóttir, is sparse and dissonant — strings that never quite resolve, echoing Nina’s own inability to find moral clarity.

The series’ power lies in its refusal to offer easy answers. It does not absolve John, nor does it fully condemn him. It does not lionize the accusers, nor dismiss them. Instead, it forces the audience to sit with discomfort — to watch Nina rationalize, deflect, protect, and finally confront the cost of her choices. The final episode, in particular, is devastating: a quiet, devastating conversation between husband and wife that contains no shouting, no tears, only the devastating weight of truth.

Critically, Vladimir has been hailed as one of Netflix’s strongest originals of the year. The Guardian called it “a razor-sharp autopsy of power, complicity, and denial,” while Variety praised Weisz as “mesmerizing — one of the finest performances on television this decade.” Viewers have responded with equal intensity: many report watching the series in a single sitting, then sitting in stunned silence afterward, unable to shake the questions it leaves behind.

At its core, Vladimir is not just about a scandal — it’s about what happens when the personal becomes political, when belief systems collide with reality, and when silence becomes its own form of violence. Rachel Weisz, in the role of a lifetime, carries the weight of that collision with devastating precision.

In an era of easy moral binaries, Vladimir refuses to let anyone — character or viewer — escape judgment. It is uncomfortable, unflinching, and unforgettable. And in the hands of Rachel Weisz, it becomes something even rarer: a work of art that forces us to look at ourselves.